For those new here, I’m currently teaching a first year writing course at Salve Regina University. It’s on Dangerous Words, and I’m specifically looking at the various facets of book bans, censorship and disinformation with my students, all while under the guise of teaching them how to write. Not only am I fascinated in this subject, but also it suits my background.1

Planning out this course was fun. I genuinely enjoyed thinking about how I was going to approach this topic, what types of texts to use, and who to read as authors. As I said previously, a few books were in the running but ultimately could not be included in my reading list. There were a whole host of other books I thought of that tangentially related to the topics of banned books, too. Since I can’t have my students read 18 books in 4 months,2 I decided to compile them into a separate resources document, which I’m now sharing with you.

I had intended to do just one post, but when I went through my notes, I had way too many books. So this will be Part 1 of 2. Part 1 includes historical books - mostly non-fiction, but some historical fiction. Many of these books came to mind because they related to Libricide - the book I am using in my course on the state sponsored destruction of books and libraries. I have read all of these books, so can at least vouch for their contents.

* Spoilers ahead* - you’ve been warned

The Monuments Men, Robert Edsel

The Monuments Men is about a group of Allied soldiers from the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program that was created during World War II to help salvage and save the art that was in danger of being destroyed because of the combat.

While this is a non-fiction book, it reads like a fiction one because of the intrigue. There were so many close saves that meant that we still have access to cultural artifacts. This very obviously relates to the course content, as it’s about people trying to save art from being destroyed. And art is treated in the broadest sense here - cathedrals, monasteries, statues, paintings, all are considered worthwhile. This book mainly focuses on Western and Northern Europe - Robert Edsel apparently had to dedicate a whole other book to just Italy. The stories are great, and there are (thankfully) lots of pictures to illustrate what works of art are being discussed.

What’s interesting is that this branch of the US Army (the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives program) was disbanded and was not reformed during any of the US’s successive war engagements. I would have loved to learn more about why the author thought this was the case, but I understand that this is out of scope for the book. It does pose an interesting question about what we as a global community consider to be art worth saving and preserving. And yes, there is a movie based on the book that stars George Clooney.

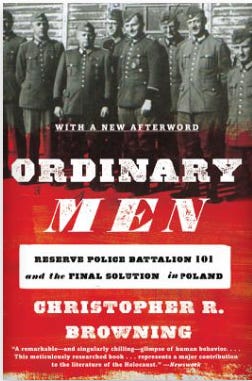

Ordinary Men, Christopher Browning

MASSIVE trigger warning for this one. I read it for a class in college, and now that I think back on it, oh boy was this a choice. Even for a course on Democracy in Europe, this was a CHOICE. I read it in 2011, and over a decade on, I still remember it, so clearly it left its mark.

That’s not to say that the book was bad, or that it was poorly written. Not at all. The subject matter was just awful. You see, Ordinary Men is about Reserve Police Battalion 101 of the German Order Police, aka one of the death squads that carried out the majority of roundups and mass shootings and deportations of Polish Jews during World War II. According to Browning’s research, this group of men was responsible for the murder of approximately 83,000 Polish Jews.3

The point of the book was to document how seemingly ‘ordinary men’ could commit such atrocious acts. Even worse? The men were told their assignment, and then were given the option to leave. If my memory serves, only 3 or 4 men declined to participate and were re-assigned elsewhere. The rest of the men in this battalion willingly carried out the acts of Holocaust. It’s a necessary look into the psychological and sociological conditions that explain human violence against each other, but it was a tough read.

I cannot in good conscience say read this book. It came to mind because when reading through the atrocities committed by regimes against books and cultural objects, I immediately thought of Ordinary Men. Libricide points out that when we hear about the destruction of books/libraries/cultural artifacts, we think of them as barbaric and one time acts. Ordinary Men helps dispel some of this self-serving mythology. Ordinary Men also brought to mind the Red Guard, which during the Chinese Cultural Revolution helped enact the Communist regime’s violent suppression of literature. Make no mistake: I am not creating an equivalency between these two groups of people. Both groups of people acted horribly in different ways. I merely bring this up as I was making connections between groups of ‘ordinary’ people carrying out heinous acts on behalf of state actors.

Speaking of the Chinese Cultural Revolution…

Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress, Dai Sijie

I don’t remember when I first read Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress, only that it was before my sophomore year in high school. Why is this relevant? We had to read this over the summer, and by that point, I had already read it once. I hadn’t read anything by Balzac at that point (and wouldn’t for another 2 years), so some of the messaging was lost on me at the time.

The book is about two young men who are sent to a remote mountain village to be ‘reeducated’ during the Cultural Revolution. They’re from the city, so there’s a level of slapstick comedy here, with the two young men being completely useless in their new rural home. They eventually befriend some of the town’s residents, and discover that the local tailor has a stash of forbidden books. (And a beautiful daughter. This won’t cause problems at all.)

If you’re not familiar with the Chinese Cultural Revolution, it was a period during the 1960s and 70s where Mao and the Communist Party attempted to purge ‘radicals’ from the Communist Party and retain ‘purity’ of the movement. It is obviously much more complex than that, but hundreds of thousands of people died, and many works of literature were banned or outright destroyed. Anything viewed as even remotely Western was forbidden, and intellectualism was scorned, to the point where many professors and scientists were killed or fled. This was made all the more jarring by the fact that China has a long and rich history of books, literature, and scholarship. The aforementioned Red Guard was a group of people, mainly students, who destroyed books, tortured local scholars, and carried out other acts of violence on behalf of the Communist Party.

The Cultural Revolution continued until Mao’s death in 1976. Mao’s successor, Deng Xiaoping, then reversed a number of Mao’s decrees, which effectively ended the Cultural Revolution. Though it only lasted a decade, the Cultural Revolution did immense damage to China. Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress is a great fictional retelling of this time in modern Chinese history.

The Three-Body Problem, Cixin Liu

I used The Three Body Problem as part of my Master’s Thesis on multi-point-of-view narratives in speculative fiction. It is the first part of a trilogy, and I can’t believe I’m about to say this, but I wouldn’t read the last two. The Three-Body Problem is an engrossing read, the last two books turn into a thought experiment about the nature of reality and the laws of physics and do not hold up as a story.4

The Three-Body Problem is hard science fiction, but a significant portion of the narrative is devoted to backstory that takes place during the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Ye Wenjie, one of our main characters, witnesses her father’s murder by Red Guards, and then is forced to join a labor camp in Mongolia. There, she makes contact with aliens, and we’re off from there. While not necessarily a book about the Chinese Revolution, that context is crucial to understand Ye’s actions, as well as her frame of mind when she contacts the aliens.

This one is also being adapted for the screen, though I am highly, highly suspicious of it. I do not doubt that the television creators of Game of Thrones5 will mess up the television adaptation (two white men adopting a story originally written in Chinese by a Chinese man for Western television, what could possibly go wrong?) so I’d read the book and skip whatever TV show is in the works. I have been proven wrong before, but until then, I will remain skeptical.

Afterparties, Anthony Veasna So

Libricide mentioned many additional examples of libricide that could not be included in the book, including the Cambodian auto-genocide committed by the Khmer Rouge. While author Rebecca Knuth decided against using that as a case study, Anthony Veasna So’s short story collection is all about the Cambodian diaspora experience, stemming from that very auto-genocide. These stories specifically center on first generation immigrants and refugees in central California. The auto-genocide and the specter of the Khmer Rouge hangs over the narratives - no matter how short the story.

This book was very well received, and was very well written. However, Veasna So died tragically young, so this will be his only publication. The stories are all encompassing, and a few of them even intersect. Though they take place in America, they are all deeply tied into the Cambodian diaspora experience.

The Secrets We Kept, Lara Prescott

The book that inspired the course from the get go. What initially caught my eye about this book was the cover - just look at that gorgeous green velvet dress - proving, once again, the indispensable nature of book designers and artists.6

The Secrets We Kept is about many things - the persecution of LGBTQ+ people in the U.S. Government in the 1950s, the distribution and publication of Doctor Zhivago and how the CIA helped, and a Greek chorus of women who worked as stenographers and typists and secretaries in the CIA.

This book follows three narratives - one focusing on Olga Ivinskaya, author Boris Pasternak’s mistress and the inspiration for Doctor Zhivago’s Lara, and then two fictional characters: a young woman named Irina who is recruited by the CIA to help carry out the mission of distributing Doctor Zhivago as well as her handler, Sally Forrester.

I was drawn to this book because of the Doctor Zhivago plot (which actually happened and is actually true)7, but the writing was…a bit lackluster. It did, however, do what most good books do: make me interested in learning more about its particular subject. For that reason alone, it ends up on this list.

The Fountainhead, Ayn Rand

I was a weird child. I’m sure everyone says that, but did you and your friends decide to wear ties to school once a month on Tuesdays because you could? And did you decide as a teenager to read Ayn Rand’s seminal text on individualism because you wanted to enter an essay contest to win an award to better your chance at college acceptance? I thought not.

I never did enter that essay contest, and no, I did not absorb most of Rand’s wilder ideas about conservatism, but The Fountainhead did have an impact on me. The scene that still resonates all of these years later is at the end of the book.

After standing trial for blowing up a building that he deemed compromise his artistic vision, architect Howard Roark goes on an impassioned speech about how an artist can only create art for themselves, can only create art for art’s sake. That’s stayed with me from an artistic perspective, but also reminded me of every extremist who has chosen to destroy art/buildings/objects/cultural heritage because they believe that ‘their’ vision for the future is the correct one. While Howard Roark is fictional and the cases in Libricide are real, the logic does come back to the same place: I am destroying something because I do not like it, and there it must be removed.

This is admittedly a more tangential connection, and I still think the principle of creating art for art’s sake is a sound one that can be applied on an individual level. But while reading Libricide, I couldn’t help but draw parallels.

And there you have it folks! Some of the (many) related books and texts that came up while I was planning out my syllabi. Maybe you have something new to add to your reading list, but at any rate, you now have a better idea of how my brain works.

Unsurprisingly, I have a chaotic academic background. Despite wanting to be a writer since I was a kid, I majored in Political Science and French, almost had a minor in Econ, was going to be a math major at one point and took through Linear Algebra, and then went on to work in tech for 10 years and get my MFA. Yeah. Every job recruiter ever is always confused by my resume.

Though I myself will certainly try.

Purportedly this is on pages 141-142. Since I do not have the book on hand I cannot check, but this is cited directly in the book and the stats can be found online. Yes, I still own this book for reasons I cannot explain.

In my own humble opinion. If you read The Dark Forest or Death’s End and felt differently, lemme know.

https://about.netflix.com/en/news/the-three-body-problem-netflix-original-series

I believe the book has a different cover now, which is a real shame, because LOOK AT THAT DRESS!!!!

https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/collection/doctor-zhivago

I wish I was taking your class. Maybe I’ll just read all the books and pretend that I’m there.