Worldbuilding is my hobby horse. It is something I love dearly - as evidenced by how hard I dove into the world of Middle Earth as a pre-teen. Though I did not do my Master’s Thesis on Worldbuilding, it’s something I continue to love and foist upon my unsuspecting writing students.1 I even ran a weekend intensive on it for

last fall.Today I want to talk about worldbuilding in connection with a few books I have recently finished reading (or am still reading currently): Ashes and Stones: A Journey Through Scotland in Search of Women Hunted as Witches, and One Summer in Savannah. As you might imagine, we’re headed for Savannah, Georgia, USA and Scotland, UK.

Worldbuilding as Writing Craft

But first, what is worldbuilding and why do we care? First of all, you might see the word spelled as worldbuilding or world-building. Either are correct, and even the dictionary has the hyphen, but I cannot be bothered to add it in so you’ll see me spell it as worldbuilding.

The official definition of worldbuilding is: “The process of developing a detailed and plausible fictional world for a novel or story, especially in science fiction, fantasy, and video games.”2

Historically, worldbuilding was most often found in the realm of Dungeons and Dragons. It’s not for naught that the definition references science-fiction, fantasy and video games. Those were the places that needed worldbuilding! How are you going to know what it’s like in Star Wars land or Middle Earth or Narnia if you don’t have everything mapped out? In this instance, I mean both literally and figuratively.

This is mainly because literary fiction (aka mimetic literary fiction, stories that reflect the current reality) take place in a world we already know. We don’t need the laws of physics or gravity explained to use because we already know them. The story is taking place somewhere on planet Earth, and while I may have never been to Russia or Syria or Japan, there are certain rules I can assume humanity will follow, in accordance with certain natural and scientific laws, based on how humans act on my side of the hemisphere. All of that work that we take for granted in literary fiction has to be done in SFF.3

Dungeons and Dragons has always involved some level of worldbuilding - the premise in and of itself depends on it. DnD character sheets are now widely recommended in fiction classes because they’re that useful. No matter the genre you’re writing in, these can help.4 DnD even has an app that lets you create your character and build a backstory for them. For the elf I’m currently playing,5 after choosing which powers she had, it became a running joke that she was a wandering meteorologist. Knowing that in and of itself means that I can now make more decisions about her behavior going forward. And based on her background, I can then make logical decisions about how she’d interact with the world.

Yes, worldbuilding covers the rote details: what the world smells like, looks like, feels like. But I argue it's what really makes fiction shine. I’ll put it to you this way: when was the last book that you sank into? I mean really sank into? That you read and forgot that time was passing? That you couldn’t put down because you were so absorbed? That you wanted to ignore the existence of the ‘real’ world? I don’t know for sure, but I bet that part of its charm was worldbuilding. Worldbuilding at its best is Tolkien - a world so expansive and detailed that it feels real. (And yes, don’t worry, we’ll get back to Tolkien.) Worldbuilding at its worst is feeling like the setting and the story itself is straight out of Central Casting. Bad worldbuilding is what throws you out of the story. Remember that bit I said a few weeks back, about the internal consistency of reality in your work? Bad worldbuilding does not have that, and has you as a reader scouring for details to prove that you’re right and the author is wrong.

I argue that worldbuilding is a more expansive version of what is normally referred to as ‘place’ or ‘setting’ within fiction and literary works. When you feel like you can walk through the town, the castle, the forest glen, that the character is in - that’s when you know the writer is in control. That’s when you know that they’ve thought through every single detail and know their characters and their stories inside and out. This can manifest in multiple ways, depending on your genre. But as much as I don’t know what Middle Earth is like, I don’t know what 1950s Russia is like. Or contemporary Syria. Or Edo Period Japan. Build the world for me, even if it’s not a fantasy tale.

You should want to have a strong world in your story regardless of the genre, because that will give your reader all the more reason to sink in and believe you. It will mean they won’t want to leave, and make your writing even more compelling.

Worldbuilding as Example

I mentioned way back in January when I checked out Ashes and Stones that I loved the cover. It’s gorgeous. I still stand by that opinion. But, the book was different than what I was expecting, and while this is partially on me, it’s also partially on how the book was marketed and described. All of this led me to think about its merits and what its strengths really were.

Ashes and Stones is described on its website as: “A moving and personal journey, along rugged coasts and through remote villages and cities, in search of the traces of those accused of witchcraft in seventeenth-century Scotland.” I took this to mean the book would be a memoir, and that we’d get Allyson Shaw’s personal journey for why she was visiting all of these monuments to witches. Sadly, that wasn’t really the case.

The book ended up being more of a road trip, with a map indicating all of the different spots and memorials that Shaw visited. Interspersed with the history and descriptions of the Scottish highlands were oblique references to Shaw’s life, and she did go into some depth about immigrating from America to Scotland and the family she left behind. However, I felt the emotional core of the book was lacking. I didn’t understand as a reader what compelled Shaw to undertake this quest in the first place. Was it valuable? Absolutely. But the overall impact was that it felt less like a narrative and more like a tour book.

What I did think work really well was Shaw’s descriptions of Scotland. I was supposed to go to Scotland in April of 2020, and I didn’t because we all know what happened. One day. Until then, I’m left with reading others’ accounts of the land of the Unicorns.6

Here’s an example of the prose:

“It's summer. I stand where perhaps Ellen stood, in this ground thick with new thistle and long grass. She would have kenned this coast in all weathers: in the summer when it was as gentle as a lake and in the winter, with the high winds and stinging salt spray.”

Reading the book, I got a great sense of the often desolate and forgotten places these memorials existed, to these women who were unfairly judged and executed. There’s a lot of history woven in between the different stops, and it’s all very illuminating. Overall, the book worked for me less as a memoir (or anything autobiographical) and more as a description of remote Scottish landscapes and its history with persecuting witches.

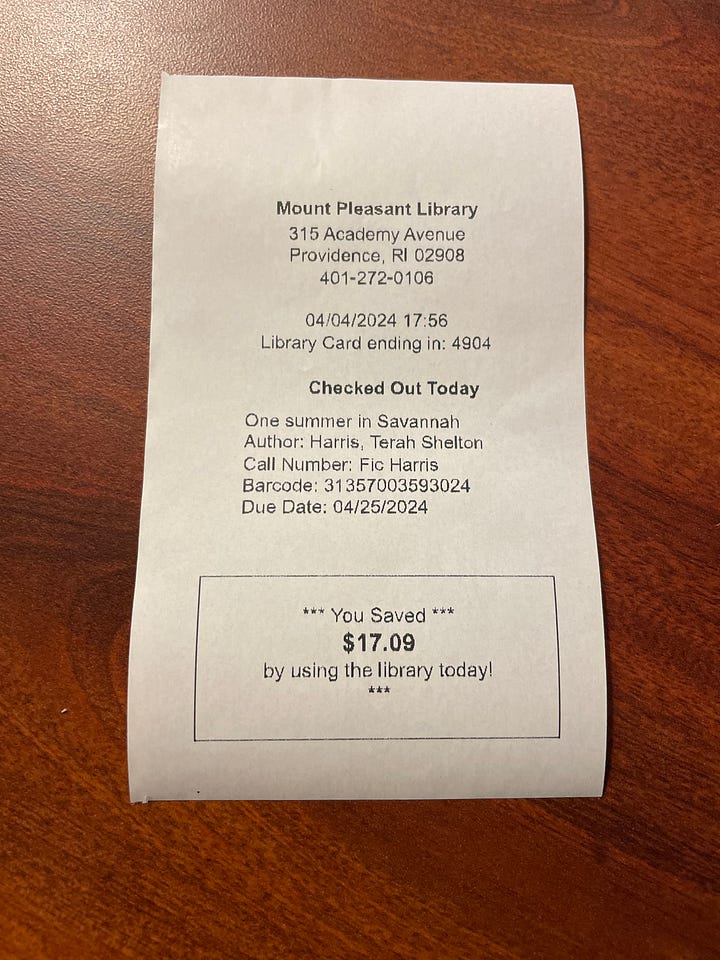

Moving from a place I’ve never been to to one I have, let’s look at One Summer in Savannah. I will admit, this is a mild bait and switch because I’ve only just started. But! The reason I checked out the book is because I’ve been to Savannah multiple times, and for an extended 6 week visit last summer for work. Before we proceed, trigger warnings for rape and sexual assault.

This is a coming home book. Sara left Savannah 8 years ago, after she was sexually assaulted. She now has a daughter, birthed from that event, and has stayed away, until her father falls ill and she’s forced to return home.

‘Coming home’ is an often used trope or theme in books. It’s a way to look at a place with new eyes, and reevaluate what you left behind. It’s also a great way to juxtapose past and present - who the character was in the past and the last time they were there, versus now. It’s also a great way to increase tension and conflict. The character left for a reason, right? So why are they coming back? Drama ensues. Like I mentioned, I picked this up because I know Savannah pretty well.7 It’s still too early for me to say whether or not this book does it successfully, or if I even recognize Savannah, but it made me immediately think of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil.

Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil is a non-fiction book by John Berendt, published in 1999 about a murder in 1981. It’s one of the most recognizeable books about Savannah. Now, while the book is non-fiction, it later came out that Berendt embellished some elements (which I’m not surprised about, things were a little too ‘neat’ in terms of the people he met during his stay in Savannah.) But, what Berendt does very, very well is get across the atmosphere of Savannah.

You see, Savannah has been around for a long while. Revolutionary War in America, 1776, long while. It also survived Sherman’s March to the Sea during the waning days of the Civil War, because the mayor of Savannah just handed over the keys to the city if Sherman would refrain from burning down the place. This means that there is a lot, A LOT, of history here. There are old buildings, and even older trees. There are memorials to Revolutionary War heroes, including fellow Pole Casimir Pulaski. All of this is to say that Savannah definitely has a feeling to it that is almost impossible to convey. Berendt does a good job of this. How?

Berendt worldbuilds. He creates Savannah as if he’s describing it to a reader who has never been there before (most of whom have not!) He uses street names, visits local residents, talks to them about the murder that happens. He goes back in history and talks about how Savannah came to be the city it is today (by the 90s standards.) He describes cemeteries, and houses, and winding streets covered with Spanish Moss. He makes Savannah as much of a character in the book as the people he’s portraying. It’s unfair to judge One Summer in Savannah against this, and I won’t be doing that. But I want to see how these books differ, how they treat Savannah as a place and character, and what kind of different worlds they conjure.

Worldbuilding can often help direct what you are trying to achieve in terms of your description. This is often a task for further drafts or editing, and not necessarily something you need to be concerned about right out of the gate. But! Part of the reason Midnight in the Garden of Good & Evil remains so iconic is because it was discussing a murder case and included mentions of the occult, cemeteries at night, and descriptions of Savannah that otherwise evoked spookiness. If a book had been describing Savannah as bright and sunny and beachy (which it is all of those things, too!) then we would feel the disconnection between the point of the story and how it was told.8 It’s a choice - what dimensions of a place are you trying to play up? What is the ‘vibe’ or atmosphere that you are trying to create? Worldbuilding can be an essential component to this and the overall framework of your story.

Worldbuilding as Practice

Just do what Tolkien did in The Lord of the Rings. The End!

I kid.

Tolkien is in a league of his own, and that’s often why he’s held up as the epitome of worldbuilding. And rightly so! There are literal Tolkien scholars who try to understand and parse all of his myriad writings. Tolkien’s world in and of itself is referred to as a ‘Legendarium:’ a literal collection of legends that Tolkien created and a step beyond worldbuilding.

As writers, we’re not looking to go to Tolkien-esque lengths.9 You can still be successful at worldbuilding without creating fictional races of Elves, Dwarves, and Men, fourteen different languages and 5,000 years of history.10 We just need a few techniques to get us started and to help us as writers identify what’s most important.

A question I often get asked in my creative writing classes is ‘how much detail is too much detail?’ This usually comes up with respect to a place that someone is describing. My answer is often: you can add more. It’s not overwhelming. But the big caveat - be judicious when you add more detail. I mean this: if we’re following your character through a market, and something life changing is about to happen to them, describe the market. Describe the smells. Tell me every single little detail, the stalls they pass, the people they recognize, all of it. If the place you’re describing is central to their character, their story, their plot? Linger a little. If they’re just walking through the market on the way to their next adventure? Have them walk right on through with no more than a few words about it.

As readers, we want to know what is most important. So, for the places and settings that matter most to your characters, make sure you know those well. And I mean really well. Here are some suggestions for where to begin:

Draw a map. Whether it’s freehand or you pay someone on the Internet to make you a fancy one, map out the character’s neighborhood, their home, the castle they live in. If they’re going to spend lots of time in it, be intimately familiar with every crevice. Think: Hogwarts.

Spend some time there. By this I mean: what does the weather look like? What happens during the seasons? If you’re writing from memory about a place or your own experience this will be easier to do, but consider how your character would act and respond to changing weather patterns or atmospheric changes. What gear would they need to survive, thrive? Think: Dune.

Think about the culture. This might involve research if you’re working with a real world culture (your own or someone else’s) or wholesale creation. Whatever it is, what community does your character belong to? What traditions might they follow? Or reject? What moral and social codes are they bound to? Think: Game of Thrones.

Remember, remember…What’s the history of this place? What details or information might be good to know? Was it a place that changed hands throughout the centuries? Is it old? New? Historical? For example, when I was in college, kids from California would be shocked at buildings that dated back to the 17th and 18th centuries in Massachusetts. Their oldest buildings were circa 1850. This will depend on whether you’re making up history or using a real place, but consider what it means for a person to inhabit a space with history, and how that history impacts them. Think: The Pillars of the Earth.

I personally have drawn maps, created family trees, and even plotted out dates on a calendar to make sure my world lines up. While it may sound like work, it can be fun! It’s a chance to really let your imagination loose - especially when you’re working in speculative genres. Otherwise if you’re writing about planet Earth then yes, you still need to respect the rules of gravity, but that’s not to say you can’t have fun with it.

What about you? Have you tried worldbuilding before? Will you incorporate any of these techniques into your own work? Let me know in the comments!

Don’t feel too bad for them. They signed up for my classes, they’re subject to my whims anyways.

Hark! A footnote doing its job!

https://www.dictionary.com/browse/worldbuilding%20

SFF = Science Fiction & Fantasy

Here are some examples to get you started, though there are hundreds available via a simple Google search.

https://media.wizards.com/2022/dnd/downloads/DnD_5E_CharacterSheet_FormFillable.pdf

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/762586149396946814/

https://in.pinterest.com/pin/get-to-know-your-character-with-these-helpful-sheets--4925880834775582/

Of course I’m an elf. There’s literally no other option here. I will never not want to be an elf because their eyesight is so good and mine is so bad.

No joke - Scotland’s emblem is the Unicorn. If you’re a Bostonian, it’s the reason there’s a unicorn on the old state house (it was part of the UK’s crest) and I think that’s one of the reasons why it got integrated into the Boston Marathon. The more you know!

I will not claim to know it better than any native Georgian, but after spending 6 weeks in a place and walking around it on foot, I got pretty comfortable.

I can also confirm Savannah is haunted as all shit. There’s a few houses that I had a visceral reaction to, and would not walk near. Also can confirm the Bird Girl statue is super haunted as well.

I mean you can, you do you. I won’t stop you!

This might be an exaggeration, but I don’t think so.