Oh hi! I’m back from my jaunt across the pond. I’m (mostly) over my jetlag, and am still getting caught up on the myriad of menial tasks that fill my daily life. Hence the late post. While it may not matter to you when this newsletter goes out, it matters to *me* if I am not punctual. Especially after growing up in a household where all of the clocks are fast.1

I’ll have some London spam for you later this week and next, but today, I wanted to talk about writing with restrictions. Or, how placing parameters on your art can lead to greater creative discoveries.

A few weeks back, I mentioned Alice Hoffman in connection with the books I bought my friend Emily. I hadn’t intended to write about Alice Hoffman and Practical Magic, but it’s actually a great exercise in artistic creation and generativity. Let me explain.

In like a Lion, in like a Lamb

I really, really need to learn to keep my mouth shut. Why am I trying to impose order on the chaos, and instead let it take me where it will? Who knows, honestly. I had a plan of what I was going to write this week, in fact, I even stated it in my last

Have you ever heard the phrase ‘the tyranny of choice’? Psychologist Barry Schwartz coined this phrase in 2004 in an article for Scientific American.2 It was specifically used in reference to the amount of choices Americans have in their day to day lives when it comes to our consumption, but it works for our purposes, too. The point of the article is that having too many choices stresses people out. When we have endless options at our fingertips, it can be anxiety provoking to make a choice. What if we choose wrong? After all, we have literally all the options available! Limiting our choices actually gives our nervous systems a break, and generally makes people happier.

Our own imaginations are boundless. We have so many choices when we’re deciding what to write. But, when we’re trying to come up with ideas, it can be overwhelming. Especially if you’re working within the speculative fiction genres.3 There are so many choices to make! What should your characters look like? What should they do? How should other people respond to them? How do they act? How do they think/feel/react to every little thing in their lives? And that’s not even taking into consideration the possible dragons/hobbits/elves of it all. The constant decision making can be exhausting as an author, much like in daily life, and putting limits on your own story can help.

These writing boundaries can be anything - word count, genre, format (especially for poetry), the laws of physics - truly, anything. But once you decide on where your limits are, you have to respect them. It then also gives you a break - you as an author can now reject anything that doesn’t fall within the ‘rules’ of your writing universe. You don’t need to worry about the history of witch trials in 18th century Scotland if your book has nothing to do with either witches, Scotland, or the 18th century.4

Put another way: author Ann Hood said in one of her talks during my MFA that she thinks of the world of her novels as a playpen. She needs to figure out the boundaries - the who, what, where, when and why essentials - before she can start writing in earnest. Without those clear demarcations, she can’t move forward and can’t ‘play’ with her characters.

I find this to be true for myself, too. After I had my (actually insane) dream a few years ago that generated my novel, I didn’t write for the first week. Instead, I spent that nebulous time around New Year’s Day 2018 just thinking and living in that dream world. Once I understood what the book was, who the characters were, and how many books there would be, I could begin writing. Without that structure, I was lost.

That doesn’t mean that I’m limiting myself to what I’m writing about within my novel: not at all. This is just to say that once certain boundaries are drawn (the timing, the place, what the characters can and cannot do) it becomes easier to know what I can and cannot do as an author. If I said the dragons can’t fly more than 50 mph in Chapter 1, then they can’t be doing that in Chapter 16 to get to the final battle faster now can they?

This logical process is referred to as the ‘internal consistency of reality.’ First coined by Tolkien in his seminal essay ‘On Fairy-Stories,’5 it refers to the idea that any logic or rule you create in your writing must be followed. If the sun rises in the east and sets in the west, you cannot change that halfway through the story just to suit your needs. Most often, it comes up for speculative fiction authors since we are, well, making everything up. But: this matters in ‘regular’ fiction, too. It’s why you as a reader get so bent out of shape when a character does something ‘out of character.’ They’ve behaved one way for 250 pages and then all of a sudden change at the end? That’s betraying their internal consistency of reality.6

So! What does this have to do with Alice Hoffman and Practical Magic? Alice Hoffman did not set out to write a series when she wrote Practical Magic in 1995. The ideas for the other 3 books (The Rules of Magic, Magic Lessons, and The Book of Magic) came later - meaning Hoffman had to respect the rules she had already set nearly two decades prior.

Spoilers Ahead

In 2019, Alice Hoffman came to speak at my MFA program. She had a new book out, Faerie Knitting, that she wrote with her daughter. As a side note, the book is lovely and includes 14 stories and associated knitting patterns. Anyways.

Alice gave a lovely talk, and answered many of our questions. I asked a question about her book covers - I hadn’t read much of her work, but I *knew* what her books looked like, since their covers were so iconic. She mentioned that she had always had a good working relationship with the designers at her publishing houses, and that for The Rules of Magic, she had one specific photo in mind of a young woman at a protest in London from the 60s, and that the designers had to go track it down to get the rights. This opened up the Practical Magic can of worms.

The book is rightly beloved, as it’s such a sweet tale at its core. Yes, there’s murder and abusive men and loss and pain, but ultimately, it’s about a group of women spanning three generations learning to love themselves and each other as best they can. I’d recommend reading both the book and watching the movie, as they’re both good, but two separate things. The movie takes a lot of liberties with the plot, something Alice Hoffman even said so herself. She recognized the movie would be it’s ‘own’ thing, and she previously worked as a screenwriter, so she doesn’t begrudge it. Plus, the movie has Sandra Bullock, Nicole Kidman, Dianne Wiest and Stockard Channing. What’s not to love?

The Rules of Magic came out in 2017, a few years prior to our talk, and Alice Hoffman talked about some of the challenges with writing backwards. The Rules of Magic is a prequel to Practical Magic, so what Hoffman set down in that first book had to be respected. That meant the curse that ancestor Maria Owens cast in 1680, that there are only 2 aunts, that there’s a big house in Salem, Massachusetts, and so on. The aunts in Practical Magic aren’t even named until the last quarter of the book, so Hoffman had to come up with backstories and personalities for characters that hadn’t originally meant to play huge roles.

Hoffman talked about how writing this new story was both thrilling and challenging. It was annoying at times to stay within the rules she had established so long ago, but it was then freeing. She didn’t have to make up more, so to speak: Hoffman had already created the rules of her universe, and so when telling this new story, she just had to respect them. It actually made writing the book easier in the end, if I recall her explanation correctly.

Hoffman then did this entire process again for Magic Lessons, which is a prequel to THOSE too books, covering the initial Maria Owens story. Again - the lore that Hoffman set down in the first two books had to be respected, so she was again working within constraints. Clearly she didn’t mind, though, because Magic Lessons came out in 2020, and the conclusion, The Book of Magic, a sequel to all of those books, came out n 2021. For those of you not familiar with how the publishing world works, Hoffman would have had to write all of those two books pretty much at the same time for them to be published within a year of each other. That doesn’t sound like someone encountering writer’s block, does it?

I’m extrapolating a bit because I saw Alice Hoffman in person in 2019, and the last two books came out during the pandemic. The point is, though, that restrictions on your writing or creative work can be freeing in the end. When you don’t have to worry about doing *everything* you can just focus on doing *one specific thing.* It allows you to go deeper into the world of your own story, without having to concern yourself with anything else.

How might you incorporate this into your own work? I’m specifically thinking of writing here, cause that’s what I do, but this applies to any form of artistic expression. Here are some ideas:

Try writing from only one character’s perspective. You cannot switch, you must stay in their point of view.

Try using only certain words. There’s an entire novel that doesn’t use words with the letter ‘e.’ Especially if you’re a poet, this could work wonders. Maybe only use words that have 3 syllables, or words that evoke sensation.

When writing description, try to incorporate all 5 senses. Every. Single. Time. Even taste.

Try a style of a writer you like. Many poets do this, you’ll often see at the top of published poems ‘written after xyz.’ It’s not plagiarism if 1) you are acknowledging where you got the inspiration from and 2) you are practicing something. There’s a reason the cliche ‘imitation is the greatest form of flattery’ exists.

Write a story that takes place in only one room.

I could keep going here, but you get the idea: once you set boundaries for yourself, it frees your mind to be creative within those restraints.

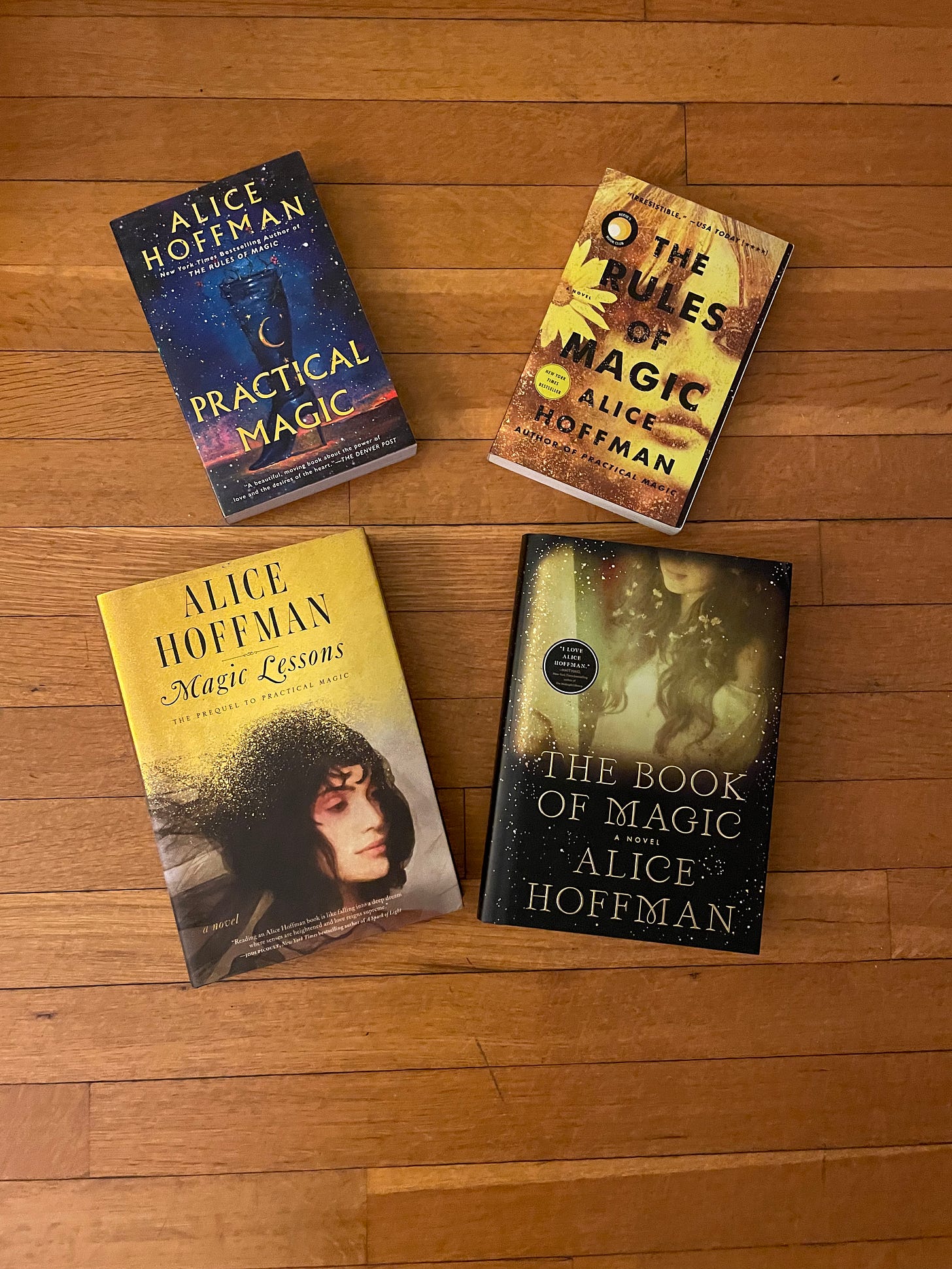

To finish, here’s my copies of the Practical Magic series and a few other tidbits that I learned from Alice Hoffman’s talk:

She discovered that her books generally follow themes of survivorship, and more specifically, women surviving difficult situations.

Working with her daughter, Lisa, was a fun and different kind of challenge. Alice wrote the stories, while Lisa provided the knitting patterns that went along with them.

Not from the talk, but the Practical Magic series can be read in any order: publication order, or chronological order of the story. So options include:

Publication Order: Practical Magic, The Rules of Magic, Magic Lessons, The Book of Magic or

Chronological Order: Magic Lessons, The Rules of Magic, Practical Magic, The Book of Magic.

That’s all for now! See you on Friday with a special vacation edition of my weekly roundup.

All of them are fast and none of them are set to each other so you really cannot trust any clock in my childhood home. Better have a watch or a phone on you.

Behold! Another footnote doing its job.

Schwartz, Barry. “The Tyranny of Choice.” Scientific American, 20 Feb. 2024, www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-tyranny-of-choice/.

As defined by Marek Oziewicz in Literature as:

"a super category for all genres that deliberately depart from imitating “consensus reality” of everyday experience. In this latter sense, speculative fiction includes fantasy, science fiction, and horror, but also their derivatives, hybrids, and cognate genres like the gothic, dystopia, weird fiction, post-apocalyptic fiction, ghost stories, superhero tales, alternate history, steampunk, slipstream, magic realism, fractured fairy tales, and more.”

Basically, anything that cannot exist in our current reality.

Oziewicz, Marek. “Speculative Fiction.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature, 29 Mar. 2017, oxfordre.com/literature/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.001.0001/acrefore-9780190201098-e-78.

Foreshadowing to what I’m reading right now.

Goodness so many footnotes doing their job today! It’s almost like I consider myself an academic or something.

Tolkien, J.R.R. University of Houston, uh.edu/fdis/_taylor-dev/readings/tolkien.html. Accessed 19 Mar. 2024.

This is also why I think the new Amazon Lord of the Rings TV show is terrible - it does not follow it’s own internal logic and abandons it whenever it suits the plot’s need. Aside from all of the other mangling it does to Tolkien’s works.